Hoofdpersonage: Balram Halwai (alias Munna, alias de witte tijger) komt uit het dorp Laxmangarh, in het district Gaya

Vader: Vikram Halwai is een riksjatrekker, sterft aan tuberculose bij gebrek aan dokters

Moeder: Sterft op vroege leeftijd, begrafenis laat stevige indruk achter op Balram.

Broer: Kishan, werkt in theehuis. Heeft niet dezelfde capaciteiten als Balram en blijft dan ook in zijn vertrouwde leefomgeving werken

Oma: Kussum, conservatieve vrouw die alle centen van Balram eist

Chinese premier: Wen Jiabao. Balram schrijft zijn hele verhaal in de vorm van brieven naar deze man.

Landheren van Gaya: Ooievaar, Everzwijn, Raaf, Buffel - vooral Ooievaar komt veel in het verhaal aangezien hij Balram's baas wordt

Twee zonen van Ooievaar: meneer Ashok (vrouw: Pink Lady - Amerikaanse) is de vriendelijke/progressieve van de twee. Meneer Mukesh (of de Maki) de conservatieve en strenge zoon.

Collega chauffeur: Vitiligolip

Klein neefje: Dharam. Is de enige die op het einde van het verhaal zijn geheim weet en perst hem daar in kleine maten mee af

De grote socialist: enorm corrupte politicus

De witte tijger - Aravind Adiga

dinsdag 13 oktober 2015

maandag 12 oktober 2015

Notities bij lezen boek

Hier zijn een paar 'symbolische' dingen die opvielen in het boek:

Hagedissen:

Het hoofdpersonage Balram Munna Halwai heeft enorm veel schrik van hagedissen. Waarom precies wordt niet verteld, maar er zijn meerdere momenten waar hij zowel als jong kind als volwassen man begint te gillen bij het zien van een hagedis.

Kroonluchters:

Balram ziet het hebben van kroonluchters als luxe en teken van rijkdom/vrijheid. Terwijl hij het boek in de vorm van brieven naar een Chinese premier schrijft zit hij in zijn eigen kantoortje met een luster. Hij wordt 'rustig' van een ventilator die het licht van de luster in stukken licht en schaduw breekt.

Paan:

Paan is een soort van pruim of 'kauw' tabak gemaakt van tabak (en nog iets) in een soort van blad gerold. Het wordt constant gebruikt door de lageren kasten in het boek. Vooral de collega taxichauffeurs van Balram en Balram zelf. Paan wordt na het kauwen uitgespuwd en laat heel herkenbare rode vlekken achter op de grond/muur/.. Mensen die veel paan gebruiken krijgen enorm rotte tanden en tandvlees.

Hagedissen:

Het hoofdpersonage Balram Munna Halwai heeft enorm veel schrik van hagedissen. Waarom precies wordt niet verteld, maar er zijn meerdere momenten waar hij zowel als jong kind als volwassen man begint te gillen bij het zien van een hagedis.

Kroonluchters:

Balram ziet het hebben van kroonluchters als luxe en teken van rijkdom/vrijheid. Terwijl hij het boek in de vorm van brieven naar een Chinese premier schrijft zit hij in zijn eigen kantoortje met een luster. Hij wordt 'rustig' van een ventilator die het licht van de luster in stukken licht en schaduw breekt.

Paan:

Paan is een soort van pruim of 'kauw' tabak gemaakt van tabak (en nog iets) in een soort van blad gerold. Het wordt constant gebruikt door de lageren kasten in het boek. Vooral de collega taxichauffeurs van Balram en Balram zelf. Paan wordt na het kauwen uitgespuwd en laat heel herkenbare rode vlekken achter op de grond/muur/.. Mensen die veel paan gebruiken krijgen enorm rotte tanden en tandvlees.

Hanenren:

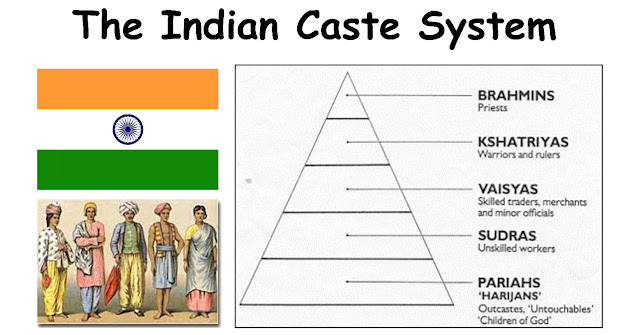

Balram vergelijkt de Indische samenleving met een hanenren. Alle Indische bedienden zitten samengepakt in kooien van kippengaas, ze pikken elkaar en zien hoe hun broeders geslacht en geplukt worden. Toch komt niemand in opstand en probeert niemand uit de ren te breken. ‘Een handvol mensen in dit land heeft de overige 99,9 procent - die in alle opzichten even sterk, begaafd en intelligent is - gedrild om in eeuwigdurende dienstbaarheid te leven.' De sleutel van dit harnas is de Indiase familie. Wie uit de ren durft te breken weet dat zijn familie kapot gemaakt zal worden. Niemand durft dit risico te nemen, alleen een witte tijger. Uiteindelijk breekt Balram uit de hanenren en stapt zo een trap omhoog om zelf baas te zijn.

Honda City:

Dit is de auto waarmee Balram zijn baas rondrijdt. In India was deze auto (rond 2008) een dure/opvallende/rijkelijke auto. Het besturen van deze auto wordt dan ook gezien als een bijna prestigieuze job, zeker voor iemand van de laagste kaste.

Nog opmerkelijk bij het chauffeur zijn: de achteruitkijkspiegel in de auto. Hierdoor houdt Balram zijn bazen constant in de gaten en probeert altijd gesprekken en ideeën op te vangen om te bij te leren en te evolueren naar iets meer dan bediende.

Geld:

Het gaat constant over geld en de waarde van geld, in India de rupee. Verdienen van geld, afpersen met geld, omkopen met geld, bedelaars geld geven, een offer aan de goden met geld,.. Balram steelt uiteindelijk 700.000 rupee van zijn baas wat veel is, wetende dat hij op zijn hoogtepunt maandelijks 4000 rupee verdiende als chauffeur. Dit gestolen geld bevindt zich ook in dure rode Italiaanse tas, die ook teken wordt van veel geld. De weken nadat hij het geld stool liep Balram er constant mee rond..

Dieren:

Mensen krijgen heel vaak dieren als bijnaam en worden daar dan ook mee beschreven.

- Balram: de witte tijger, een heel zeldzaam dier.

- 4 corrupte landeigenaars van zijn geboorte streek: ooievaar, buffel, de raaf en het everzwijn

- strenge broer van zijn baas: de maki

- waterbuffels: zijn belangrijke dieren in een familie

- hagedis: heeft Balram schrik van

Wat hier vaak mee in verband gebracht wordt is het de-wet-van-de-jungle principe, dieren maken andere dieren kapot. De indiaanse samenleving is het oerwoud.

De grote socialist:

De grote socialist is de naam van een ongelooflijk corrupte politicus in India die al zijn stemmen koopt. “Wij hebben dan wel geen riolering, drinkwater en olympische gouden medailles, maar wij hebben wél democratie”. In ‘het donker’, zoals Balram de lagere kasten noemt, is die democratie immers een farce. Iedereen blijkt er voor de Grote Socialist te stemmen. Hun stemmen zijn al lang voor de verkiezingsdatum verkocht en de stembiljetten ingevuld. De man haalt 2341 stemmen op 2341 en wanneer een stumper toch zo dom is om aan het stemhokje op te dagen, wordt hij door de mannen van de Grote Socialist vakkundig in elkaar geramd. “Ik ben de trouwste kiezer van India,” schrijft Balram fijntjes, “en ik heb nog nooit een stemhokje van binnen gezien”.

De grote socialist maakt propaganda met het beeld van een twee handen die een ketting kapot trekken als symbool voor de ontketening van de dictatuur en recht in eigen handen nemen. Natuurlijk enorm hypocriet omdat er van democratie niks in huis komt. Balram gebruikt het beeld echter ook als symbool voor zijn ontketening uit 'het donker'.

zondag 11 oktober 2015

Artiekel/interview over "De Witte Tijger"

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2008/oct/16/booker-prize

Roars of anger

Aravind Adiga's debut novel, The White Tiger, won the Booker prize this week. But its unflattering portrait of India as a society racked by corruption and servitude has caused a storm in his homeland. He tells Stuart Jeffries why he wants to expose the country's dark side

How do you get the nerve, I ask Aravind Adiga, to write a novel about the experiences of the Indian poor? After all, you're an enviably bright young thing, a middle-class, Madras-born, Oxford-educated ex-Time magazine correspondent? How would you understand what your central character, the downtrodden, uneducated son of a rickshaw puller turned amoral entrepreneur and killer, is going through?

It's the morning after Adiga, 33, won the £50,000 Man Booker award with his debut novel The White Tiger, which reportedly blew the socks off Michael Portillo, the chair of judges, and, more importantly, is already causing offence in Adiga's homeland for its defiantly unglamorous portrait of India's economic miracle. For a western reader, too, Adiga's novel is bracing: there is an unremitting realism usually airbrushed from Indian films and novels. It makes Salman Rushdie's Booker-winning chronicle of post-Raj India, Midnight's Children (a book that Adiga recognises as a powerful influence on his work), seem positively twee. The Indian tourist board must be livid.

Adiga, sipping tea in a central London boardroom, is upset by my question. Or as affronted as a man who has been exhausted by the demands of the unexpected win and the subsequent media hoopla can be. Guarded about his private life, he looks at me with tired eyes and says: "I don't think a novelist should just write about his own experiences. Yes, I am the son of a doctor, yes, I had a rigorous formal education, but for me the challenge of a novelist is to write about people who aren't anything like me." On a shortlist that included several books written by people very much like their central characters (Philip Hensher, for example, writing about South Yorkshire suburbanites during the miners' strike, or Linda Grant writing about a London writer exploring her Jewish heritage), the desire not to navel-gaze is surprising, even refreshing.

But isn't there a problem: Adiga might come across as a literary tourist ventriloquising others' suffering and stealing their miserable stories to fulfil his literary ambitions? "Well, this is the reality for a lot of Indian people and it's important that it gets written about, rather than just hearing about the 5% of people in my country who are doing well. In somewhere like Bihar there will be no doctors in the hospital. In northern India politics is so corrupt that it makes a mockery of democracy. This is a country where the poor fear tuberculosis, which kills 1,000 Indians a day, but people like me - middle-class people with access to health services that are probably better than England's - don't fear it at all. It's an unglamorous disease, like so much of the things that the poor of India endure.

"At a time when India is going through great changes and, with China, is likely to inherit the world from the west, it is important that writers like me try to highlight the brutal injustices of society. That's what writers like Flaubert, Balzac and Dickens did in the 19th century and, as a result, England and France are better societies. That's what I'm trying to do - it's not an attack on the country, it's about the greater process of self-examination."

That, though, makes Adiga's novel sound like funless didacticism. Thankfully - for all its failings (comparisons with the accomplished sentences of Sebastian Barry's shortlisted The Secret Scripture could only be unfavourable) - The White Tiger is nothing like that. Instead, it has an engaging, gobby, megalomaniac, boss-killer of a narrator who reflects on his extraordinary rise from village teashop waiter to success as an entrepreneur in the alienated, post-industrial, call-centre hub of Bangalore.

Balram Halwai narrates his story through letters he writes, but doesn't send, to the Chinese premier, Wen Jiabao. Wen is poised to visit India to learn why it is so good at producing entrepreneurs, so Balram presumes to tell him how to win power and influence people in the modern India. Balram's story, though, is a tale of bribery, corruption, skulduggery, toxic traffic jams, theft and murder. Whether communist China can import this business model is questionable. In any event, Balram tells his reader that the yellow and the brown men will take over the world from the white man, who has become (and this is where Balram's analysis gets shaky) effete through toleration of homosexuality, too slim and physically weakened by overexposure to mobile phones.

Halwai has come from what Adiga calls the Darkness - the heart of rural India - and manages to escape his family and poverty by becoming chauffeur to a landlord from his village, who goes to Delhi to bribe government officials. Why did he make Halwai a chauffeur? "Because of the whole active-passive thing. The chauffeur is the servant but he is, at least while he's driving, in charge, so the whole relationship is subverted." Disappointingly, Adiga only knows of the Hegelian master-slave dialectic from reading Nietzsche's Genealogy of Morals. But that dialectic is the spine of his novel: the servant kills his master to achieve his freedom.

The White Tiger teems with indignities masquerading as employee duties. Such, Adiga maintains, is India - even as Delhi rises like a more eastern Dubai, call-centres suck young people from villages and India experiences the pangs of urbanisation that racked the west two centuries ago. "Friends who came to India would always say to me it was a surprise that there was so little crime and that made me wonder why." Balram supplies an answer: servitude. "A handful of men in this country have trained the remaining 99.9% - as strong, as talented, as intelligent in every way - to exist in perpetual servitude." What Balram calls the trustworthiness of servants is the basis of the entire Indian economy; unlike China, he reflects, India doesn't need a dictatorship or secret police to keep its people grimly achieving economic goals.

"If we were in India now, there would be servants standing in the corners of this room and I wouldn't notice them," says Adiga. "That is what my society is like, that is what the divide is like." Adiga conceived the novel when he was travelling in India and writing for Time magazine. "I spent a lot of time hanging around stations and talking to rickshaw pullers." What struck him was the physical difference between the poor and the rich: "In India, it's the rich who have problems with obesity. And the poor are darker-skinned because they work outside and often work without their tops on so you can see their ribs. But also their intelligence impressed me. What rickshaw pullers, especially, reminded me of was black Americans, in the sense that they are witty, acerbic, verbally skilled and utterly without illusions about their rulers."

It is not surprising then that the greatest literary influences on the book were three great African-American 20th-century novelists - Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin and Richard Wright. "They all wrote about race and class, while later black writers focus on just class. Ellison's Invisible Man was extremely important to me. That book was disliked by white and blacks. My book too will cause widespread offence. Balram is my invisible man, made visible. This white tiger will break out of his cage."

For Indian readers, one of the most upsetting parts of that break-out is that Halwai casts off his family. "This is a shameful and dislocating thing for an Indian to do," says Adiga. "In India, there has never been strong central political control, which is probably why the family is still so important. If you're rude to your mother in India, it's a crime as bad as stealing would be here. But the family ties get broken or at least stretched when anonymous, un-Indian cities like Bangalore draw people from the villages. These really are the new tensions of India, but Indians don't think about them. The middle- classes, especially, think of themselves still as victims of colonial rule. But there is no point any more in someone like me thinking of myself as a victim of you [Adiga has cast me, not for the first time, as a colonial oppressor]. India and China are too powerful to be controlled by the west any more.

"We've got to get beyond that as Indians and take responsibility for what is holding us back." What is holding India back? "The corruption, lack of health services for the poor and the presumption that the family is always the repository of good."

Our time is nearly over. Adiga doesn't know how he will spend his prize money, isn't even sure if there's a safe bank in which to deposit it. Doesn't he fear attacks at home for his portrayal of India? After all, the greatest living Indian painter, MF Husain, lives in exile. "I'm in a different position from Husain. Fortunately, the political class doesn't read. He lives in exile because his messages got through, but mine probably won't."

Adiga, who says he has written his second novel but won't talk about it ("It might be complete crap, so there's no point"), flies home to Mumbai today to resume his bachelor life. His most pressing problem is that Mumbai landlords don't let flats to single men. Why? "They think we're more likely to be terrorists. I'd just like to say, through your pages, that I am not. In fact, if you check the biographies of Indian terrorists you'll find they are mostly family men who are well-off. It's a trend that needs to be investigated."

Possibly in a new novel by Adiga, yet again analysing the unbearably poignant torments of the emerging new India. Ideally, though, with jokes.

zaterdag 10 oktober 2015

Individualisme: research

Benadrukt het belang van het individu. Onafhankelijkheid en zelfvoorziening staan centraal. Anarchisme wordt vaak aan individualisme gelinkt omdat men in een anarchistische staat het ultieme individu is – geen verantwoordelijkheden, plichten etc

Individualisme houdt ook een sterke band met het liberalisme. Daarnaast wordt individualisme ook vaak gekoppeld aan de Amerikaanse droom en het dollar-teken. Americanization, individualisme en liberalisme zijn dus onlosmakelijk verbonden. Dit zijn ook drie van de tekens in het boek.

bron

Abonneren op:

Reacties (Atom)